Restarting our Innovation Engine

Reforming Research Funding Can Reignite Productivity and Prosperity

Improving our standard of living fundamentally depends on driving innovation. Yet, the engine of innovation, reflected in productivity growth, has slowed significantly in recent decades. This isn't just an abstract economic concern; it directly impacts our collective prosperity. This slowdown stems from multiple factors: ideas are becoming harder to find, the sheer volume of existing knowledge creates burdens for new innovators, and ironically, the very systems we use to fund research often stifle the most groundbreaking work through excessive bureaucracy. To reignite progress, we need a fundamental shift, moving away from rigid oversight towards investing more trust and resources in our most brilliant and creative minds, especially early in their careers.

Our Productivity Problem and Impact on Innovation

The engine that drives improvements in our standard of living is labor productivity growth. This process translates economic output into higher real incomes and greater prosperity for society. Rising labor productivity results directly from innovation, the creation and application of new ideas, technologies, and processes.

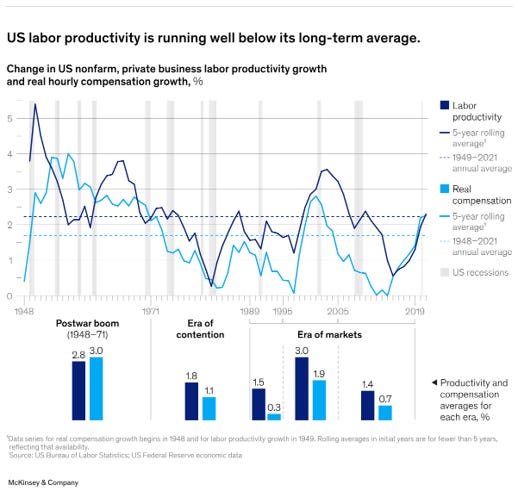

However, as documented in a 2023 McKinsey Global Institute report, our productivity engine has been sputtering since 2005. Growth has fallen to a lackluster 1.4 percent annually, a significant drop from the 2.2 percent average seen in the decades following World War II.

This slowdown represents a massive opportunity cost. McKinsey estimates that simply returning to our historical 2.2 percent growth rate could add a cumulative $10 trillion to US GDP by 2030. That's equivalent to an extra $15,000 for every household. Fostering the conditions for robust productivity gains through innovation is not just an economic abstraction; it is a critical imperative for continuing to raise living standards.

Why Innovation is Getting Harder

Diminishing Research Returns

Why is labor productivity dragging? One significant reason is that our current approach to generating innovation appears to yield diminishing returns. Despite enormous increases in research inputs, the results are less impactful than in the past. Inflation-adjusted R&D investment in the US has increased twenty-threefold since the 1930s, growing at 4.3% annually. Yet, the resulting growth in aggregate total factor productivity (TFP), which measures how efficiently inputs like labor and capital are used and serves as a proxy for innovation and technological progress, has remained disappointingly stable or even slightly declined. This stagnation matters immensely because TFP growth, representing genuine improvements in how we produce things rather than just using more resources, is the fundamental driver of long-term economic expansion and sustained increases in our standard of living.

This sharp fall in research productivity suggests that ideas are becoming substantially harder to find across the economy. The sobering implication is that maintaining even constant economic growth now requires research efforts to double roughly every 13 years, merely to offset this increasing difficulty.

The Burden of Knowledge

We can also expect it to become even more difficult to drive innovation in the future due to what economist Benjamin F. Jones labeled in 2005 the "Burden of Knowledge." This concept stems from simple observations: nobody is born an expert, and the total expertise within any field accumulates over time.

Early innovations often represent the easier-to-find "low-hanging fruit." As a field matures, reaching the expanding knowledge frontier demands progressively greater investment in education and time. Individuals must master vast amounts of existing knowledge before they can even begin to make novel contributions.

This escalating difficulty presents two core challenges. First, sustaining innovation requires ever-increasing investments in money, time, and human capital. Second, as these investments rise to tackle more complex problems built upon vast prior knowledge, they may become incrementally less productive, facing diminishing returns.

How Our Funding System Hinders Breakthroughs

The Burden of Bureaucracy

While ideas become harder to find, our approach to funding science has simultaneously shifted incentives away from the most innovative work. Following World War II, the United States massively expanded its investment in scientific research, a commitment reflected in today's federal R&D spending of around $200 billion annually.

Though substantial in absolute terms, this funding represents a smaller share of GDP (roughly 0.7-0.8%) compared to historical peaks. Still, the US contributes about 25-30% of global R&D. This vast investment inevitably attracts intense scrutiny and political concerns about accountability, famously exemplified by Senator William Proxmire's "Golden Fleece Award" targeting perceived waste.

This pressure has fueled a dramatic increase in bureaucratic oversight. Researchers now face extraordinarily complex grant applications and burdensome reporting requirements. This administrative load forces them to dedicate significant time, perhaps up to half, away from the lab bench and towards paperwork.

Consequently, the funding system increasingly rewards not necessarily the most groundbreaking ideas, but the safest, most incremental proposals. These are the projects articulated by the most adept grant writers, potentially stifling the very high-risk, high-reward research needed for true innovation leaps.

The Cost of Missed Opportunities: Katalin Karikó

The experience of Nobel laureate Katalin Karikó offers a stark illustration of how potentially revolutionary science can be stifled by these conventional funding mechanisms. For years at the University of Pennsylvania, Karikó relentlessly pursued her pioneering ideas on messenger RNA (mRNA), believing in its therapeutic potential.

Despite submitting countless grant proposals, she consistently failed to secure government funding. Her unconventional approach deviated from prevailing scientific dogma and lacked the preliminary data often demanded by peer review committees focused on predictable outcomes.

This lack of funding led to professional setbacks, including demotion, and ultimately forced her to leave academia for the private sector. The eventual, world-changing success of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 dramatically underscores the pitfalls of a system that can struggle to recognize and support the high-risk, paradigm-shifting ideas championed by persistent, visionary individuals.

Rethinking How We Fund Science

Understanding Scientific Revolutions

Our challenge is multi-faceted: increase spending to keep pace, manage complexity, reduce administrative burdens, and, crucially, take more chances on brilliant minds pursuing breakthroughs. In his influential 1970 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas S. Kuhn argued that science doesn't always advance through steady accumulation. Fields operate under dominant "paradigms," shared frameworks defining problems and methods. Scientists engage in "Normal Science," solving puzzles within that paradigm.

However, this process uncovers "anomalies" that the paradigm can't explain. Persistent anomalies trigger a "crisis," leading to new thinking and eventually a "scientific revolution" – a fundamental shift in understanding. Our current funding system, optimized for "Normal Science," may inadvertently hinder the emergence of these revolutionary shifts.

Embracing Metascience

In their just-published book “Abundance,” Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson point to a critical paradox: Despite being the world's largest science funder, the US government lacks a systematic understanding of how progress is best nurtured. We invest vast sums without robust evidence on optimal strategies.

An emerging field, "metascience," aims to rectify this by rigorously studying science itself. It involves experiments comparing funding models: Are specific project grants best? Or open-ended grants to brilliant individuals? Or funding long-term labs?

Currently, we lack clear answers on which approaches yield the greatest return on investment. Discovering which models best catalyze innovation is essential for ensuring our research investments translate into meaningful advancements.

A Model for Change: The V Foundation

Alternative models do exist. My wife and I have been proud supporters of The V Foundation for Cancer Research. As a national foundation, its mission is to achieve Victory Over Cancer® by funding crucial, cutting-edge cancer research nationwide.

What resonates with me is their distinct funding philosophy. They don't focus solely on established pathways with guaranteed gains. Instead, they courageously take chances, prioritizing truly innovative, high-risk ideas and specifically backing brilliant, early-career scientists.

They provide critical funding for concepts often lacking extensive preliminary data but possessing the bold potential to become the next transformative cancer breakthrough. This embodies a commitment to investing in promising individuals and their visions, offering a potential model for fostering crucial innovations.

To truly revitalize the engine of prosperity, we must confront the dual challenges of diminishing research returns and a funding system increasingly biased against bold ideas. The evidence suggests that innovation is getting harder, demanding more resources just to maintain progress. Simultaneously, bureaucratic hurdles consume valuable researcher time and favor safe bets over potential breakthroughs. Rethinking our approach by studying what actually works ("metascience") and by adopting models that invest more directly in talented individuals with visionary ideas, like the V Foundation does, offers a pathway to unlocking the next wave of innovations essential for enhancing our standard of living.

What about the demise of good early and not-so-early education and our ever more endangered supply of bright/educated minds? Figures on what has happened to our children after the pandemic are discouraging. Not that they were great before. And what happens if we attract less and less intellect from outside our borders? None of the factors for advancement can work without the “raw material.” Are we counting on AI to be the substitute?

Universities have done a good job of teaching the current knowledge and expanding scientific knowledge by painstaking incremental research. Innovation is best done by the private sector where the latest research is "reduced to practice" in useful economic products that are unforeseen by research scientists. c.f. DARPA and Bill Gates. Universities will reassume a dominant role in expanding scientific knowledge and serendipitous innovative breakthroughs when they reduce the proportion of their expenditures going to bloated administrative functions and social engineering and redirect more funding to all types of scientific research and teaching