Are we living in an age of antiglobalization?

Adapting to populism while preserving the benefits of globalization

Traveling on a train in Portugal recently, I overheard an American declare to his companion, "we truly are living in an age of antiglobalization." This statement, uttered in the scenic Portuguese countryside in an era where Portugal is enjoying strong economic growth, piqued my curiosity about the current state of globalization.

The modern era of globalization began after World War II, with the establishment of international institutions like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (later becoming the World Trade Organization). Globalization accelerated in the latter half of the 20th century as economists like Jagdish Bhagwati and Paul Krugman developed theories explaining the benefits of free trade and economic integration. Policymakers, influenced by these ideas, began dismantling trade barriers.

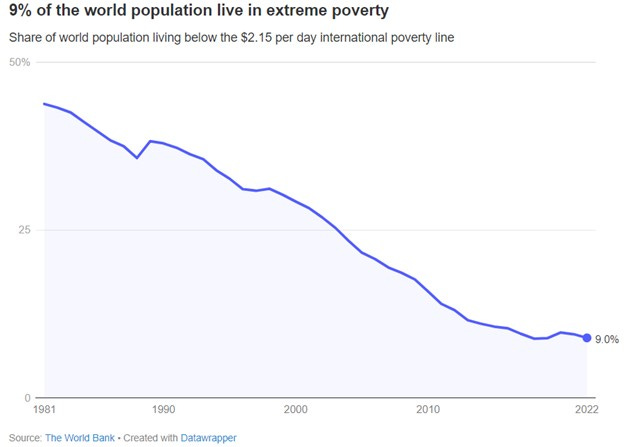

The importance of globalization in raising the standards of living around the world cannot be overstated. According to the World Bank, the proportion of the global population living in extreme poverty fell from 36% in 1990 to 9% in 2022, a decline largely attributed to economic growth fueled by global trade and investment and only briefly interrupted by the COVID pandemic. Countries like China and India have seen dramatic improvements in their economies and living standards through participation in the global economy. For instance, China's GDP per capita grew from $309 in 1980 to $10,500 in 2020, a staggering increase.

Since the fall of the fascist dictatorship in 1974, Portugal has significantly benefited from globalization. The country's integration into the European Union in 1986 was a pivotal moment, opening up new trade opportunities and investments which modernized Portugal's infrastructure. Portugal's economy has diversified beyond traditional sectors like textiles and agriculture. Portugal has enjoyed strong growth in sectors such as renewable energy, information technology, and automotive manufacturing. Tourism has become a major contributor to the economy, with Portugal leveraging its climate, culture, and coastline to attract visitors like us from around the world. Improvements in productivity, competitiveness, and tourism have raised living standards for the Portuguese people.

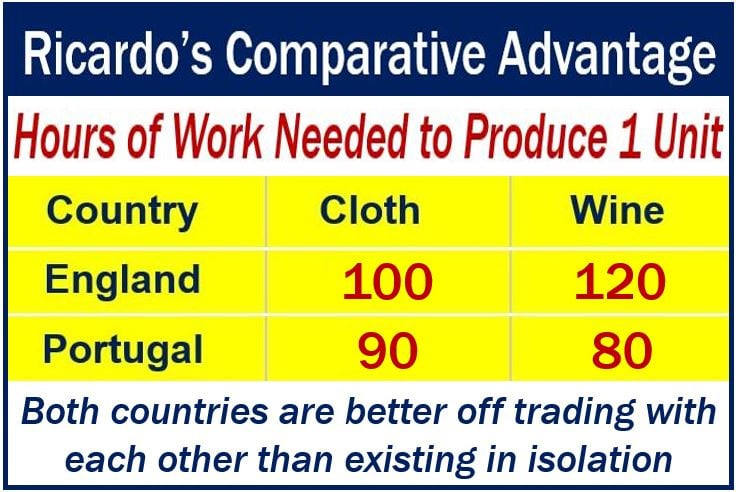

Globalization has been so effective in raising standards of living worldwide due in part to the concept of comparative advantage, a country's ability to produce a particular good or service at a lower opportunity cost than its trading partners. This principle, first articulated by economist David Ricardo in the early 19th century, explains why trade can benefit all parties involved, even when one country is more efficient at producing everything. Ricardo famously illustrated this concept using the example of English cloth and Portuguese wine. Even if Portugal could produce both wine and cloth more efficiently than England, both countries would still benefit from trade if Portugal specialized in wine production (where its relative efficiency was greatest) and England focused on cloth manufacturing. For instance, Portugal might be able to produce wine with less labor than it takes to make cloth, while England might find cloth production relatively more efficient than winemaking. By specializing and trading, both countries can increase their total output and consumption beyond what they could achieve in isolation. This specialization allows each country to maximize its productive efficiency, leading to increased overall output and lower prices for consumers in both nations. Comparative advantage is a critical element of what makes globalization effective in raising standards of living because it encourages countries to focus on what they do best, fostering innovation, efficiency, and the optimal allocation of resources on a global scale.

However, in recent years, there has been new sentiment against globalization. Populist movements in many countries have incorporated antiglobalist rhetoric into their platforms. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in global supply chains, leading to shortages of critical goods and prompting calls for greater self-sufficiency.

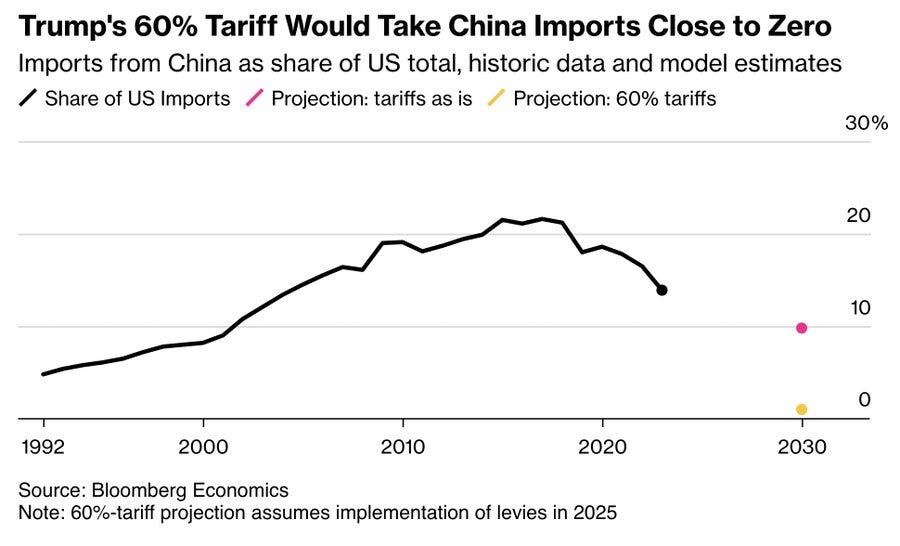

Geopolitical tensions have posed challenges to globalization. The United States, under the Trump administration, engaged in trade disputes with China and implemented policies to reduce dependence on foreign suppliers. Trump’s proposal of a 60% tariff on all China imports, which, if implemented, would take China imports down to close to zero, goaded the Biden administration into a new tariffs on Chinese imports, including EV batteries, computer chips, and medical products. Similarly, China has emphasized its "dual circulation" strategy, aiming to reduce reliance on foreign markets while remaining open to trade and investment. None of this is good for either country.

Environmental concerns have added another layer of complexity to the globalization debate. The European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, set to be fully implemented by 2026, aims to price the carbon content of imports from less climate-ambitious countries. This move reflects growing awareness of the environmental costs associated with global trade

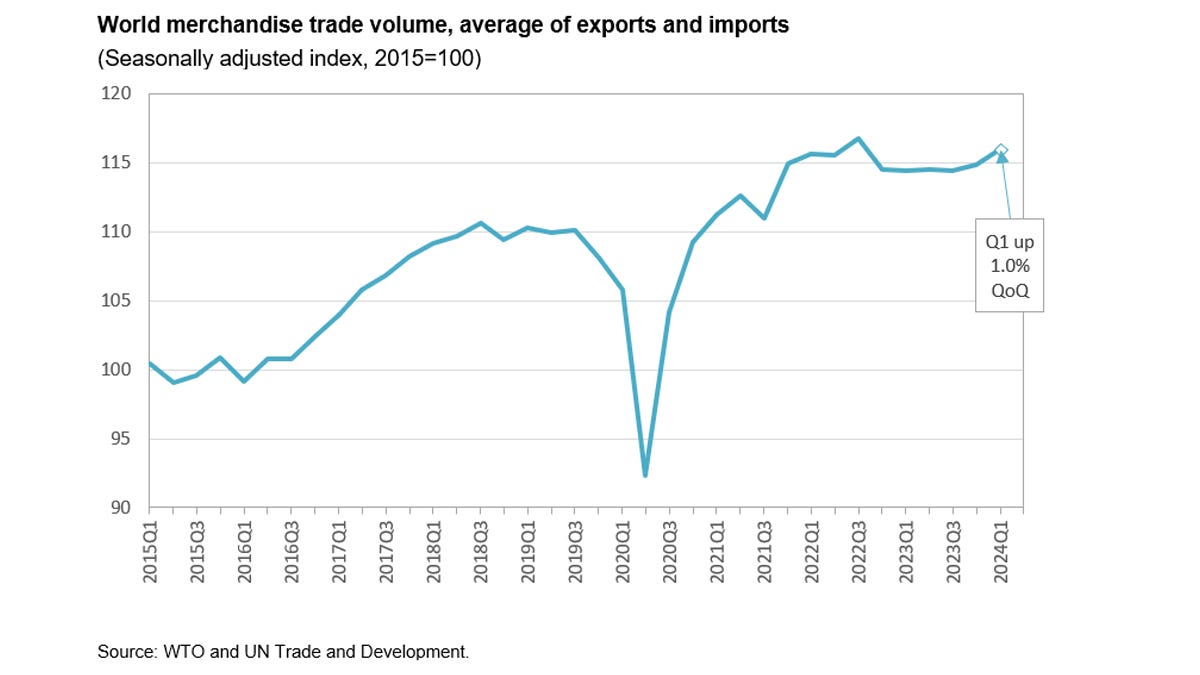

Despite these challenges, it would be premature to declare the end of globalization. The global economy remains highly interconnected. The WTO reports that world merchandise trade volume grew by 1.0% in the first quarter of 2024, demonstrating resilience in the face of geopolitical tensions and lingering pandemic effects. Moreover, digitally enabled trade in services continues to grow rapidly, with the OECD estimating that digital trade accounted for 6.6% of global GDP in 2022.

The digital revolution and advancements in areas like artificial intelligence are inherently global in nature. These technologies are facilitating new forms of global collaboration and commerce that transcend traditional borders. For instance, the global market for AI is projected to grow from $387.45 billion in 2022 to $1,394.30 billion in 2029, a compound annual growth rate of 20.1%.

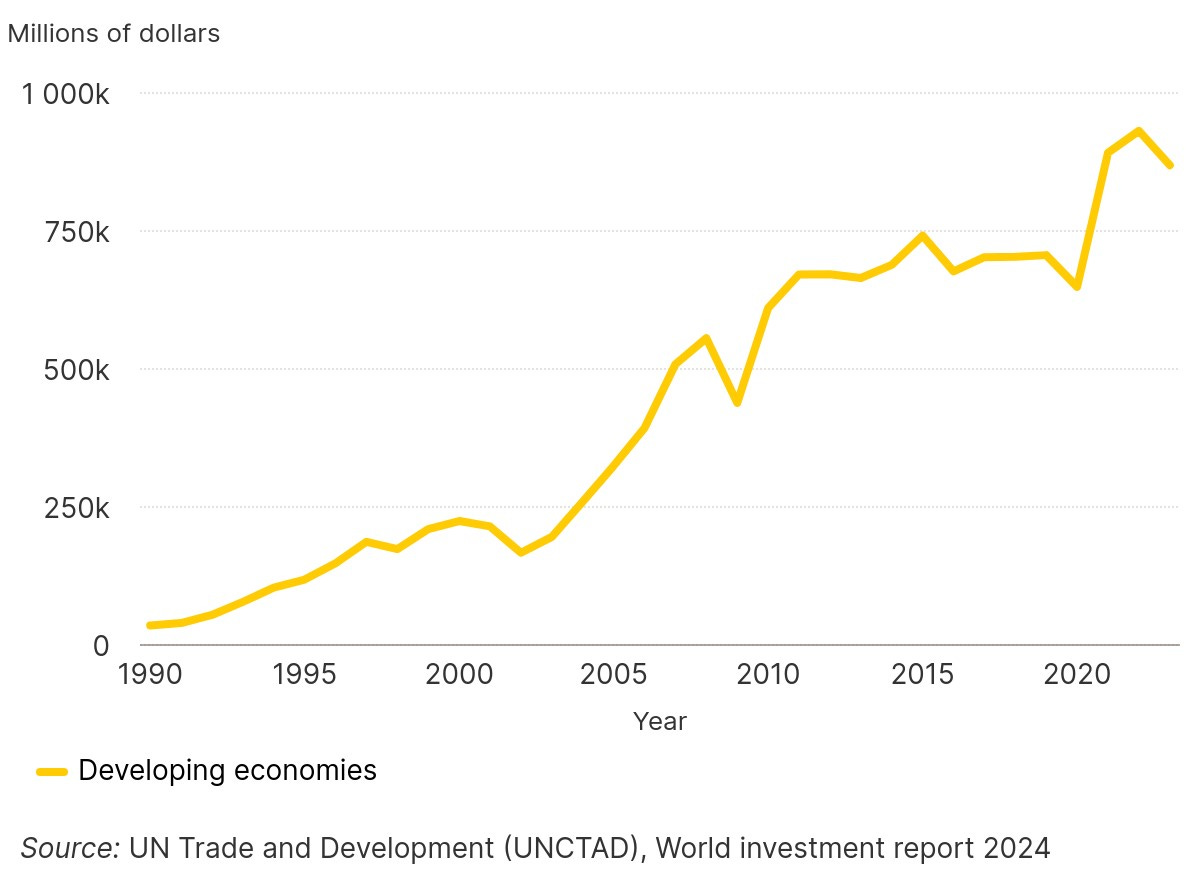

Many parts of the world continue to benefit significantly from international openness and globalization. Developing countries, in particular, have seen substantial gains. The United Nations reports that foreign direct investment to developing economies reached a $867 billion in 2023.

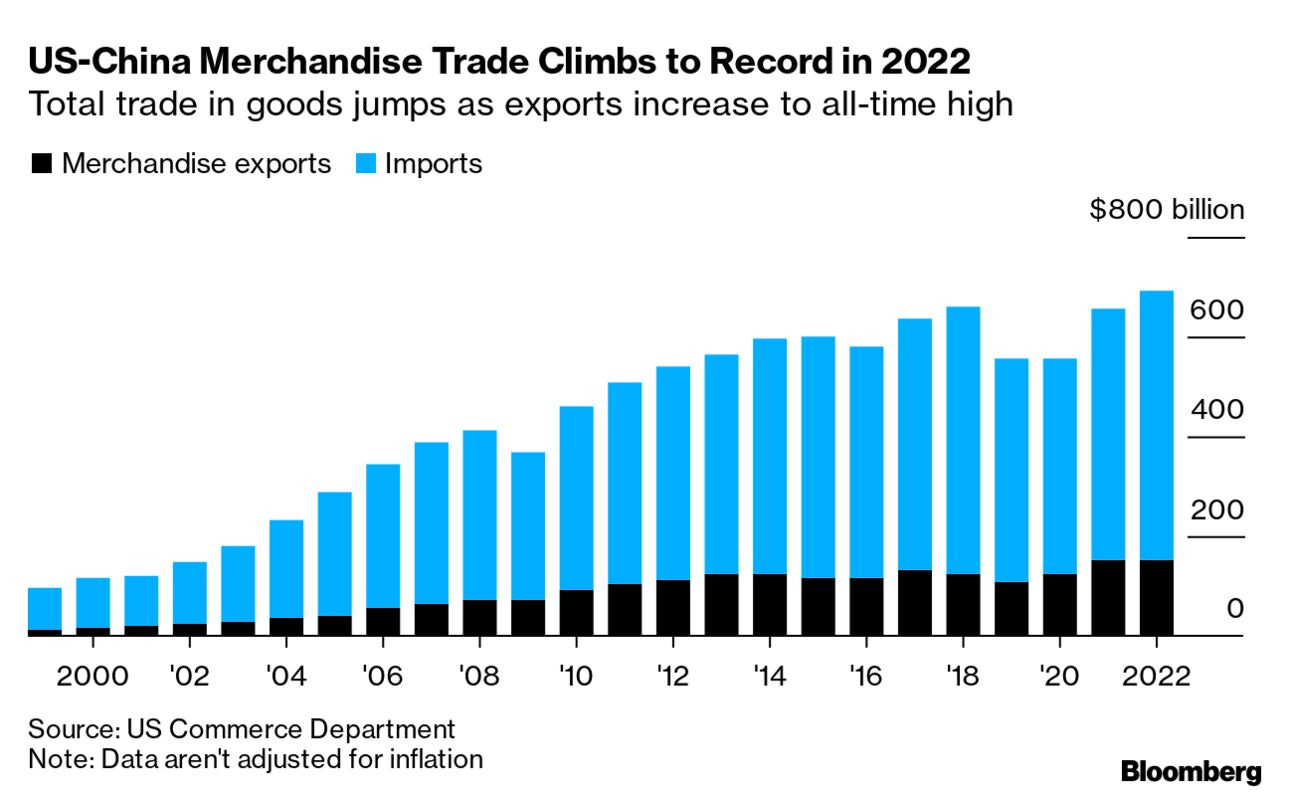

While tensions exist between major powers, there's also a trend towards pragmatism. The U.S. and China, despite being strategic rivals, maintain significant economic ties. In 2022, total trade between the two countries reached $758 billion, demonstrating the deep economic interdependence that persists despite political tensions.

While we are certainly witnessing challenges to globalization, it's an overstatement to say we're living in an "age of antiglobalization." Instead, we're seeing a recalibration. Countries and businesses are seeking to balance the benefits of international engagement with the need for resilience and security. The path forward will involve addressing legitimate concerns raised by globalization's critics while preserving the benefits of international cooperation and exchange. This may require updating international institutions, developing more inclusive economic policies, and finding innovative ways to address global challenges like climate change and technological disruption.

As we navigate this complex landscape, it's crucial to maintain a nuanced understanding of globalization's impacts and potential. By doing so, we can work towards a more equitable and sustainable global economy that benefits all.

Peace through understanding.

Wow, was this published just last July?! It seems like an eon ago.

Globalization has been a path to wealth for many countries, most notably the United States.

The much-warned-of ascendancy of China to the world's #1 economy that was so common in the 1990s and 2000s hasn't happened, the US economy has continued to grow and remains #1.

Parts of the US economy shrunk while others have grown. As you wrote, the concept of comparative advantage describes why this happens. But in net the US economy is the best in the world.

An open and vibrant trading economy is also in the world's national security interests. "When goods don’t cross borders, soldiers will."

It is in our national interests to have core capabilities vibrant in the US. I would like to see more advanced semiconductor manufacturing done here; it is also important to have the metal/mineral fabrication done within our borders, as well as many pharmaceuticals, to name a few. Government policy, when well thought out and executed competently, can drive for targeted industries to retain/rebuild core capabilities in the US, while still retaining the many advantages of open trade.

And because SUBSTACK doesn't allow images or charts in their comments, here is a table:

GDP by Country: 1994 2004 2014 2022

USA $7.3T $12.2T $17.6T $25.5T

China $0.6T $2.0T $10.5T $18.0T

Germany $2.2T $2.8T $3.9T $4.3T

https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/country/by-country/startyear/ltst/endyear/ltst/indicator/NY-GDP-MKTP-CD

Good analysis of the benefits of free trade and globalization in a perfect world. Unfortunately many countries subsidize production to sell products below cost to capture markets; take VAT taxes off exports, but add them to imports; and employ regulations or tax credits to protect local producers from foreign competition. Obviously, this provokes retaliation and free trade suffers.